17.2 Gross Anatomy of Urine Transport

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the ureters, urinary bladder, and urethra, as well as their location, structure, histology and function

- Compare and contrast male and female urethras

- Describe the micturition reflex

- Describe voluntary and involuntary neural control of micturition

Rather than start with urine formation, this section will start with urine excretion. Urine is a fluid of variable composition that requires specialised structures to remove it from the body safely and efficiently. Blood is filtered and the filtrate is transformed into urine at a relatively constant rate throughout the day. This processed liquid is stored until a convenient time for excretion. All structures involved in the transport and storage of the urine are large enough to be visible to the naked eye. This transport and storage system not only stores the waste, but it protects the tissues from damage due to the wide range of pH and osmolarity of the urine, prevents infection by foreign organisms and for the male, provides reproductive functions.

Urethra

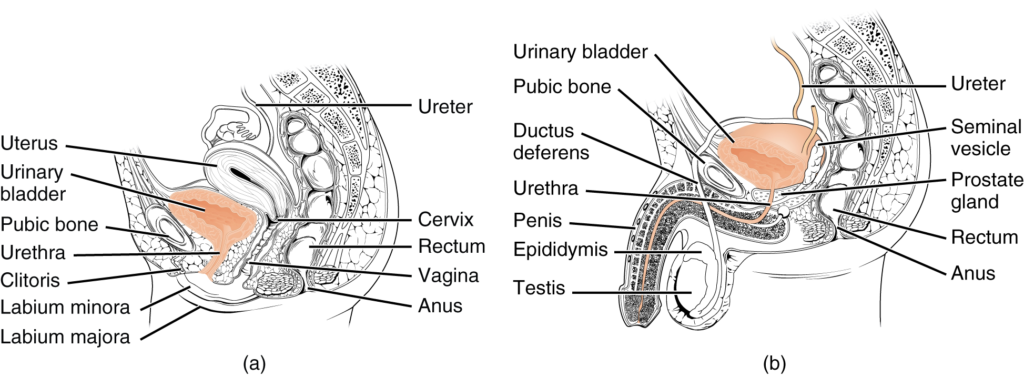

The urethra transports urine from the bladder to the outside of the body for disposal. The urethra is the only urologic organ that shows any significant anatomic difference between males and females; all other urine transport structures are identical (Figure 17.2.1).

The urethra in both males and females begins inferior and central to the two ureteral openings forming the three points of a triangular-shaped area at the base of the bladder called the trigone (Greek tri- = “triangle” and the root of the word “trigonometry”). The urethra tracks posterior and inferior to the pubic symphysis (see Figure 17.2.1a). In both males and females, the proximal urethra is lined by transitional epithelium, whereas the terminal portion is a nonkeratinised, stratified squamous epithelium. In the male, pseudostratified columnar epithelium lines the urethra between these two cell types. Voiding is regulated by an involuntary autonomic nervous system-controlled internal urinary sphincter, consisting of smooth muscle and voluntary skeletal muscle that forms the external urinary sphincter below it.

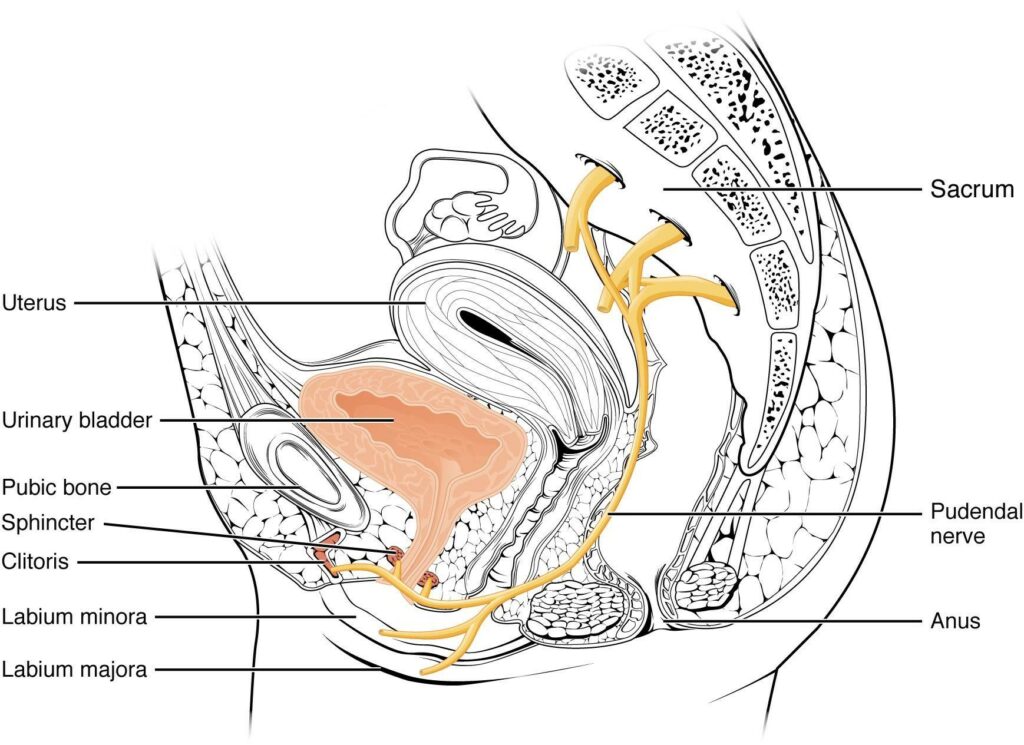

Female Urethra

The external urethral orifice is embedded in the anterior vaginal wall inferior to the clitoris, superior to the vaginal opening (introitus), and medial to the labia minora. Its short length, about 4 cm, is less of a barrier to faecal bacteria than the longer male urethra and the best explanation for the greater incidence of UTI in women. Voluntary control of the external urethral sphincter is a function of the pudendal nerve. It arises in the sacral region of the spinal cord, travelling via the S2–S4 nerves of the sacral plexus.

Male Urethra

The male urethra passes through the prostate gland immediately inferior to the bladder before passing below the pubic symphysis (see Figure 17.2.1b). The length of the male urethra varies between men but averages 20 cm in length. It is divided into four regions: the preprostatic urethra, the prostatic urethra, the membranous urethra and the spongy or penile urethra. The preprostatic urethra is very short and incorporated into the bladder wall. The prostatic urethra passes through the prostate gland. During sexual intercourse, it receives sperm via the ejaculatory ducts and secretions from the seminal vesicles. Paired Cowper’s glands (bulbourethral glands) produce and secrete mucus into the urethra to buffer urethral pH during sexual stimulation. The mucus neutralises the usually acidic environment and lubricates the urethra, decreasing the resistance to ejaculation. The membranous urethra passes through the deep muscles of the perineum, where it is invested by the overlying urethral sphincters. The spongy urethra exits at the tip (external urethral orifice) of the penis after passing through the corpus spongiosum. Mucous glands are found along much of the length of the urethra and protect the urethra from extremes of urine pH. Innervation is the same in both males and females.

Bladder

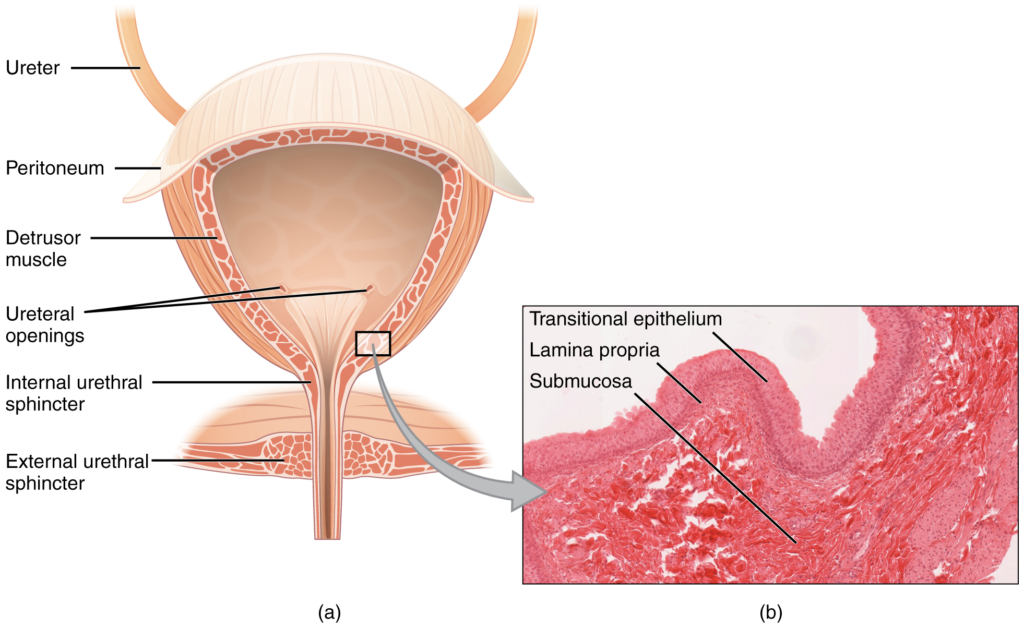

The urinary bladder collects urine from both ureters (Figure 17.2.2). The bladder lies anterior to the uterus in females, posterior to the pubic bone and anterior to the rectum. During late pregnancy, its capacity is reduced due to compression by the enlarging uterus, resulting in increased frequency of urination. In males, the anatomy is similar, minus the uterus and with the addition of the prostate inferior to the bladder. The bladder is partially retroperitoneal (outside the peritoneal cavity) with its peritoneal covered “dome” projecting into the abdomen when the bladder is distended with urine.

The bladder is a highly distensible organ comprised of irregular crisscrossing bands of smooth muscle collectively called the detrusor muscle. The interior surface is made of transitional cellular epithelium that is structurally suited for the large volume fluctuations of the bladder. When empty, it resembles columnar epithelia, but when stretched, it “transitions” (hence the name) to a squamous appearance (see Figure 17.2.2). Capacity of the bladder varies with age and volumes in adults can range from nearly zero to 500–600 mL.

The detrusor muscle contracts with significant force in the young. The bladder’s strength diminishes with age, but voluntary contractions of abdominal skeletal muscles can increase intra-abdominal pressure to promote more forceful bladder emptying. Such voluntary contraction is also used in forceful defaecation and childbirth.

Micturition Reflex

Micturition is a less-often used, but proper term for urination or voiding. It results from an interplay of involuntary and voluntary actions by the internal and external urethral sphincters. When bladder volume reaches about 150 mL, an urge to void is sensed but is easily overridden. Voluntary control of urination relies on consciously preventing relaxation of the external urethral sphincter to maintain urinary continence. As the bladder fills, subsequent urges become harder to ignore. Ultimately, voluntary constraint fails and may result in incontinence, which will occur as bladder volume approaches 300 to 400 mL.

Normal micturition is a result of stretch receptors in the bladder wall that transmit nerve impulses to the sacral region of the spinal cord to generate a spinal reflex. The resulting parasympathetic neural outflow causes contraction of the detrusor muscle and relaxation of the involuntary internal urethral sphincter. At the same time, the spinal cord inhibits somatic motor neurons, resulting in the relaxation of the skeletal muscle of the external urethral sphincter. The micturition reflex is active in infants but with maturity, children learn to override the reflex by asserting external sphincter control, thereby delaying voiding (potty training). This reflex may be preserved even in the face of spinal cord injury that results in paraplegia or quadriplegia. However, relaxation of the external sphincter may not be possible in all cases, and therefore, periodic catheterisation may be necessary for bladder emptying.

Nerves involved in the control of urination include the hypogastric, pelvic and pudendal (Figure 17.2.3). Voluntary micturition requires an intact spinal cord and functional pudendal nerve arising from the sacral micturition centre. Since the external urinary sphincter is voluntary skeletal muscle, actions by cholinergic neurons maintain contraction (and thereby continence) during filling of the bladder. At the same time, sympathetic nervous activity via the hypogastric nerves suppresses contraction of the detrusor muscle. With further bladder stretch, afferent signals travelling over sacral pelvic nerves activate parasympathetic neurons. This activates efferent neurons to release acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junctions, producing detrusor contraction and bladder emptying.

Ureters

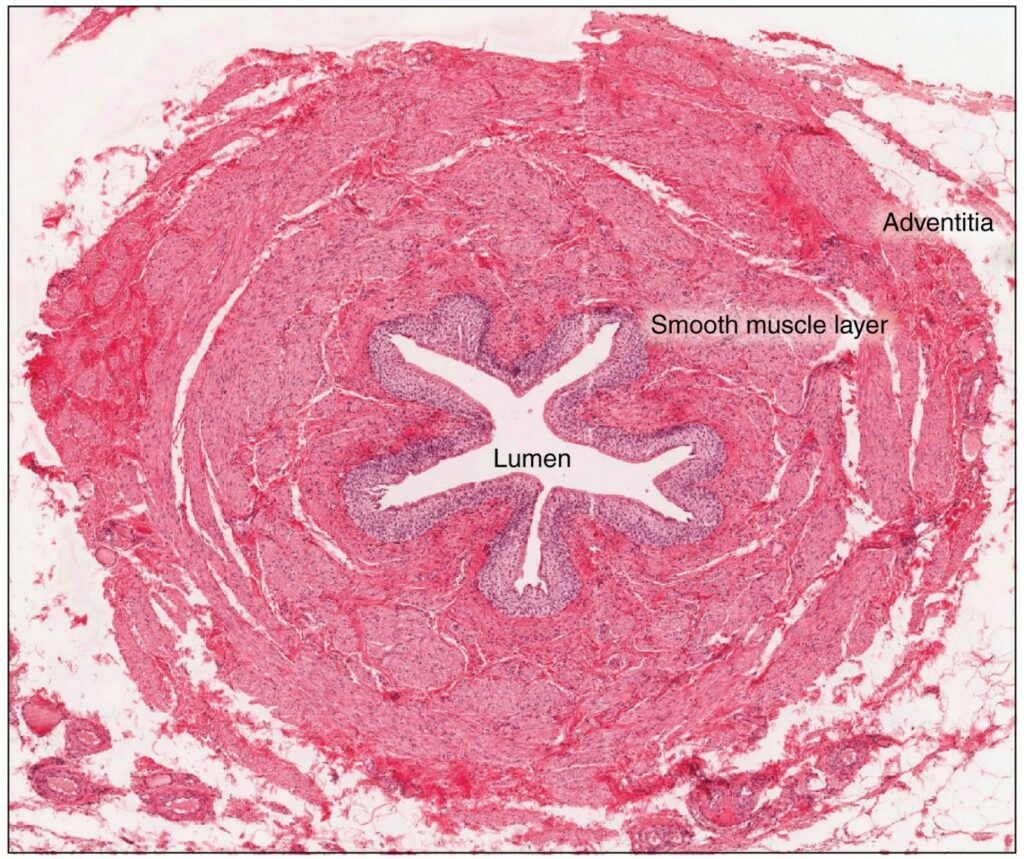

The kidneys and ureters are completely retroperitoneal, and the bladder has a peritoneal covering only over the dome. As urine is formed, it drains into the calyces of the kidney, which merge to form the funnel-shaped renal pelvis in the hilum of each kidney. The hilum narrows to become the ureter of each kidney. As urine passes through the ureter, it does not passively drain into the bladder but rather is propelled by waves of peristalsis. As the ureters enter the pelvis, they sweep laterally, hugging the pelvic walls. As they approach the bladder, they turn medially and pierce the bladder wall obliquely. This is important because it creates a one-way valve (a physiological sphincter rather than an anatomical sphincter) that allows urine into the bladder but prevents reflux of urine from the bladder back into the ureter. Children born lacking this oblique course of the ureter through the bladder wall are susceptible to “vesicoureteral reflux,” which dramatically increases their risk of serious UTI. Pregnancy also increases the likelihood of reflux and UTI.

The ureters are approximately 30 cm long. The inner mucosa is lined with transitional epithelium (Figure 17.2.4) and scattered goblet cells that secrete protective mucus. The muscular layer of the ureter consists of longitudinal and circular smooth muscles that create the peristaltic contractions to move the urine into the bladder without the aid of gravity. Finally, a loose adventitial layer composed of collagen and fat anchors the ureters between the parietal peritoneum and the posterior abdominal wall.

Section Review

The urethra is the only urinary structure that differs significantly between males and females. This is due to the dual role of the male urethra in transporting both urine and semen. The urethra arises from the trigone area at the base of the bladder. Urination is controlled by an involuntary internal sphincter of smooth muscle and a voluntary external sphincter of skeletal muscle. The shorter female urethra contributes to the higher incidence of bladder infections in females. The male urethra receives secretions from the prostate gland, Cowper’s gland, and seminal vesicles as well as sperm. The bladder is largely retroperitoneal and can hold up to approximately 500–600 mL urine. Micturition is the process of voiding the urine and involves both involuntary and voluntary actions. Voluntary control of micturition requires a mature and intact sacral micturition centre. It also requires an intact spinal cord. Loss of control of micturition is called incontinence. The ureters are retroperitoneal and lead from the renal pelvis of the kidney to the trigone area at the base of the bladder. A thick muscular wall consisting of longitudinal and circular smooth muscle helps move urine toward the bladder by way of peristaltic contractions.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

Click the drop down below to review the terms learned from this chapter.